Flying ants and other myths…

October 20, 2012

Systematically gathered and analysed evidence is important, because it challenges myths and prejudices that we all have a tendency to develop. Sometimes these myths are important for innovation or policy, but other times they are just plain interesting. In the latter class, a fascinating study was reported by the BBC this week. The study shows that, contrary to a widely held myth, flying ants do not all emerge on the same day each summer. In fact emergence is spread over a more extended period.

As well as an interesting and counter-intuitive result, the study caught my eye as it is an example of citizen science. The data were recorded by members of the public, providing the researchers with an extended capacity to observe the ant behaviour. The study would have been far too expensive and difficult to carry out without this contribution from volunteers. This type of engagement is a fantastic way to get interesting research done, and also engage those outside of the research community in the process.

Great as citizen science is, we do need to be careful not to start believing another myth: that citizen science is limited to volunteers acting as data collectors or sophisticated image processors. Citizen science also needs to encompass involving people from outside the research community in shaping the nature and direction of research. While there have some moves to address this, another myth stands in the way; that allowing greater public involvement will reduce the quality or value of the research. Perhaps we need some experiments to put that myth to the test too.

Text-mining and open access

October 18, 2012

There is an excellent opinion piece in the latest edition of Research Fortnight by Professor Doug Kell on text-mining and open access. As for many the article will be behind a pay-wall (the irony…) I thought I would summarize the argument and post a few quotes here.

The argument goes like this:

- New research findings are being added to the body of literature at a rate that means it is impossible for anyone to read it all, let alone assimilate and make sense of it all. The only solution is to use text-mining.

- There are clear benefits for researchers, business and policy-makers in using text-mining of the scientific literature. For example a recent report from JISC concludes that “there is clear potential for significant productivity gains, with benefit both to the sector and to the wider economy”.

- But for text-mining to be effective access is needed to the full text. Abstracts are not enough, and for rapid interpretation of new research embargo periods are a problem.

And here are some key paragraphs from the article:

The PubMed database records two new peer-reviewed papers in the life sciences every minute. Across all the sciences, the number is five.

Such is the rate at which scholarly papers are produced that only computers can read them all. As a result, text-mining techniques are infiltrating every field of research, from genomics to the social sciences and humanities. Historians are using text mining to analyse court records from the Old Bailey. Business has been mining newswires since the 1980s to acquire competitive intelligence and today companies use text mining, including of social media, to discover what customers think of their products and services.

[…]

To get the most from text mining requires open access to the literature. And it requires it as soon after publication as possible. In the life sciences, six months—the maximum embargo allowed in Research Councils UK’s policy on ‘green’ open access—is a very long time.

This is one reason why the research councils’ policy on open access announced this July made the ‘gold’ model the preferred route. Pursuing gold open access will help the UK to get ahead of the curve in exploiting the opportunities, including text mining, that come from open access.

Reflections on The Geek Manifesto

May 26, 2012

As I read Mark Henderson’s new book “The Geek Manifesto” I found my mood alternating between enormous optimism and nagging pessimism. Perhaps this is spot on for a book that seeks to inspire geeks (and I would count myself within this group) to action; at times it is inspiring, at others the challenge to make a difference seems overwhelming. But while in some senses the book covers familiar ground, it does an excellent job in bringing together material and arguments in a form that is clear and inspiring. As I read, there were some broad issues that I kept returning to. These aren’t criticisms of the book, as such, but areas were I think there is some room for further reflection and debate.

- Science or evidence? A key thrust of the argument in the book is that policy-making should be better informed by assessment of the evidence, and Henderson is careful to remind us on a number of occasions that this evidence often stretches beyond the boundaries of the natural sciences. The word ‘science’ is often, though, used as a shortcut for ‘evidence’ and there is a risk that some will take this shortcut seriously. Similarly, the importance of factors beyond the evidence in guiding political decision-making are mentioned, but the take-home may again be that science trumps everything else. And there is certainly a strong thrust through the book that the scientific method is centrally important, especially in the guise of randomised trials. While I don’t disagree that there are opportunities to use these approaches more in public policy, it is also important not to discourage other types of analytical approach (qualitative social science, or historical analysis, for example) and to avoid developing a false hierarchy of approaches to evidence.

- Ethics. This is a book about ethics in the sense that it is concerned very much with ‘doing the right thing’. For me, a strong utilitarian ethic underpins the argument suggesting that we need to formulate policies that are in the interests of the majority. I am sympathetic to this argument, but I think it is important to acknowledge that there is considerable debate about this ethical approach and it is relatively easy to construct scenarios where a strict adherence to utilitarian ethics raises real dilemmas. Alternative ethical approaches, like rights-based ethics, would take a rather different approach to many of the issues covered. For example, should people have the right to choose homeopathic treatment if that’s what they want? I think we need to open up debates like this, which sit uncomfortably with the strict evidence-led approach.

- Evidence-based science policy. A really important point that Henderson stresses, but that bears repeating, is that it is essential that the geeks are themselves always strictly evidence-led. Nowhere is this more important than in the field of science and innovation policy, where we need to be zealous in demanding the highest quality evidence to inform policy. And implicit in this, is that we need to follow the evidence even if it disagrees with our preconceptions and prejudices. This is, after all, what being evidence-led is all about. I am not convinced that the scientific community is always as open to evidence about its own practice as it ought to be. I also wonder whether the research community would be supportive of randomised trials if, say, the Research Councils were to suggest that a new policy approach would be applied to a random sample of research grant applications to investigate how well it worked. But maybe I am wrong about this.

Overall, I would strongly recommend “The Geek Manifesto“. It’s a good read, very thought-provoking and an excellent contribution to the debate about evidence and policy.

I will be debating these and other points with Mark Henderson, James Wilsdon and others on Tuesday 29 May at the Science Policy Research Unit in Sussex University. Come and join in!

There is an understandable focus on the future in science policy discussions. We are often concerned with how investment in science and other research will contribute to future economic growth, health and well-being, and sustainable development. How should we invest now to bring about the future we want to see? What types of science should we support? How should that science be conducted? But the evidence that we draw upon is often about the past. What has been the result of previous investment? What impact did policies or the environment have previously? The science of science policy is largely a historical science.

Too often the analysis of the past that is used in discussions about science policy is flawed, based on anecdote or partial and distorted narratives. These stories are modified to fit present prejudice and don’t always provide the reliable representation of the past that we need for evidence-based policy making for science.

The Haldane Principle is a classic example of a myth about science policy itself. It is held up as the great bastion of UK science policy, but often without a critical analysis of where it comes from or its history. This thorough essay by David Edgerton should be compulsory reading for all researchers and people working in science policy. The result of this lack of historical context is that debates hinge around the adherence, or not, to this mythical principle which casts scientific decision making into an us (scientists) versus them (politicians) framework. Instead we need to replace this with a more nuanced debate about decision making that recognises that there are many other voices to be balanced in the question of who decides on science.

Poor understanding of the historical context also leads to inaccurate notions of how scientific discovery has happened in the past. There is a persistent narrative that science contributes most when scientists are left to pursue their curiosity, unencumbered by considerations of application. But is this really always true?

No. For example, there is an excellent discussion of Maxwell’s work on electromagnetism by Simon Schaffer in Nature from last year. Two quotes sum up the conclusions:

Maxwell’s magnificent work of the 1860s is an excellent example. Rather than a stately progression from abstract theory to solid application, it was the product of a web of markets, technologies, labs and calculators in the workshop of the world.

In sum, On Physical Lines of Force is an odd text to use as example of the unyielding purity of physical science. Maxwell’s formulae did not appear in their most familiar form until almost 25 years after its publication. The four famous equations linking electromagnetic forces and fluxes owe their elegant and economical vector form to a brilliant London telegraphist, Oliver Heaviside. He published them in 1885 in The Electrician, a trade journal for electrical engineers and businessmen.

As Peter Medawar wrote in the 1960s, we need to be careful not to get carried away by an excessively romantic notion of the pursuit of science. His thinking was explained and amplified by Tom Webb recently.

Sound analysis is also important in understanding how innovation has worked in the past. For example challenge prizes for innovation are often mentioned in the context of Harrison and the Longitude Prize. But as the Board of Longitude project shows the story is rather more complicated than is often appreciated, and even that “There was no such thing as the Longitude Prize“.

Historical evidence is important for the development of science policy, but we need to make sure it is the best evidence available. Experts in the history of science have a key role to play in the policy-making process of today.

New questions for science policy

April 12, 2012

What are the key outstanding questions in science policy? This challenging question has recently been addressed in a paper describing work led by the Cambridge Centre for Science and Policy (CSaP). The resulting list is interesting and comprehensive and will be a useful guide both to those working on science policy in academia and science policy practitioners. There have been some criticisms that the work is insufficiently reflective, or that there are already, at least partial, answers to some of the questions in the literature, but I think the authors are to be congratulated in pulling together a comprehensive list.

Interestingly, a collaborative process was used to generate the list, building on earlier work to develop similar lists for other disciplines. The paper is an excellent example of what can be achieved by drawing on a range of experts in a systematic manner. I can’t help, though, feeling that an opportunity was missed. The process was entirely focussed on experts, but could have really benefitted from including some public dialogue. What do people think about how research evidence is used in policy making? How do people want to see scientific evidence balanced with other factors? Exploring these and other issues with people whose expertise and experience lies outside of the science policy world would have led to some refinement of the research questions, or indeed resulted in the identification of new areas for research. Some may think that engaging the public with abstract policy issues is too difficult, but I don’t believe this is the case. Indeed we need to open up the processes of science policy more, and public engagement is an important aspect. Our recent experience at RCUK is that, while challenging, it is perfectly feasible to engage on research policy. Working with Sciencewise, we have recently carried out a public dialogue on data openness that is generating useful insight for policy development. The question of how we can further improve the approaches that we use to hold useful dialogues with members of the public on science policy matters is itself an interesting matter for further research.

There is also real scope for a second phase to the CSaP project. The research questions in the paper are focussed largely on ‘science for policy’ – how scientific evidence can be effectively used in policy making – and this is clearly an area of strong public interest. But equally I think that a similar exercise would be really valuable to explore the key questions for ‘policy for science’. The Science of Science Policy initiative in the US has made an excellent start in this direction, especially with its research roadmap (pdf). This roadmap sets out some high level questions for research, framed largely from the perspective of policy makers in science and innovation policy. The roadmap could form the basis of further work, along the lines of the CSaP study, to further elaborate the questions and bring them into a European context. Of course this would only be valuable if it stimulates further research targeted at the questions that emerge, but strengthening the evidence base on which we make research policy decisions is likely to bring significant rewards. As was recently argued by Pierre Azoulay in Nature:

It is time to turn the scientific method on ourselves. In our attempts to reform the institutions of science, we should adhere to the same empirical standards that we insist on when evaluating research results.

Are universities ‘museums of knowledge’?

February 29, 2012

If you are interested in the role and future of universities then I recommend that you read the recent essay in the Guardian by Stefan Collini. Trailing his new book, Collini makes some interesting and thought-provoking comments that are worth reading whether you agree or not.

There is one aspect of Collini’s arguments that I strongly disagree with – the notion that the central role of universities is as repositories and guardians of knowledge and culture.

Some, at least, of what lies at the heart of a university is closer to the nature of a museum or gallery than is usually allowed or than most of today’s spokespersons for universities would be comfortable with.

[Universities] have become an important medium – perhaps the single most important institutional medium – for conserving, understanding, extending and handing on to subsequent generations the intellectual, scientific, and artistic heritage of mankind.

I believe that the idea of universities being primarily ‘museums of knowledge’ is both wrong and politically dangerous.

To cast universities as the repositories of knowledge ignores the complex and distributed way in which knowledge is now stored in the world. Through the internet codified knowledge is stored in many places and available in many more, so to suggest that knowledge is somehow associated with a particular set of locations seems strange. The distribution and access to knowledge also means that the guardianship, interrogation and use is not restricted, anymore, to the academy. There is expertise of all sorts to be found outside of universities, giving a collective aspect to the intellectual endeavour that extends beyond the campus or the quadrangle.

Take Wikipedia for example. Its authors are drawn from a range of backgrounds including, but not restricted to, academia. While Wikipedia is not without its problems, it is broadly accurate in capturing knowledge and ideas about the world, and has a responsiveness that more traditional approaches to the curation of knowledge can only dream about.

Linking the idea of the university to the idea of the museum is also politically dangerous. Collini himself mentions that this concept has a ‘backward-looking’ feel and counters that the idea also emphasises the importance of considering the university as an investment for future generations. But the idea of the museum raises a difficult issue for funding. While I accept that funding is not easy for universities, and that there is controversy around the idea of students themselves paying more of the costs, universities are much better funded than the museum sector. Casting universities as museums may make convincing politicians that they are worthy of public investment on a large scale even harder. The notion also risks reinforcing a stereotypical image of the university as a dry, out of touch institution. This is unfair to both universities and museums, but it is essential that the public and politicians see universities as they really are – progressive, up-to-date and outward-looking institutions with a strong committment to making a difference in the world.

The challenge is to communicate the reality of the modern university sector to politicians, policy-makers and the public. We need a new narrative that covers the diverse range of ways that our universities benefit society. This needs to include the very real economic benefits, but not be limited to them. We also need to make real for people the contributions that universities make to our culture, to the coherence of society and to the communities in which they are located. Celebrating the modern university is key to securing its future.

Eyes on the prize?

November 21, 2011

High profile prizes for science and engineering have been making the headlines recently. Last week the Royal Academy of Engineering announced a new international prize for excellence in engineering, the Queen Elizabeth prize. Worth a million pounds to the winner, the ambition is to make this the equivalent of the Nobel Prize for engineering. Like the Nobel, this prize has a broad scope and contrasts with prizes focussed on addressing specific challenges. The idea of awarding prizes for advances in science and engineering has an illustrious history, and there is good evidence that prizes can act as strong incentives for innovation (Tim Harford‘s recent book, Adapt, covers this point in detail).

It is also claimed that prizes like this inspire young people, but I am not convinced. The problem is that these big international prizes are so rare that they tend to encourage the view that only a tiny minority of researchers can reach the peak of their profession. This is just not a fair reflection of the process of research, where most researchers make contributions to the advancement of knowledge. Indeed many of the advances celebrated by high profile prizes depend upon advances made by researchers who are not awarded the prize.

But I also think there is a problem with visibility and engagement. While there may be a brief news item when the prize is announced, there is limited opportunity to engage people with the science, the scientists or the prize process itself. I am always struck by the contrast between these science and research prizes, and the coverage of other prizes, like the Turner prize, the Man Booker Prize and even the Stirling Prize. In these cases there is intense media attention, and often vigorous public debates. For example, this year’s Man Booker triggered discussions about the nature of quality literature; is readability and accessibility necessary, sufficient, or perhaps even antagonistic to, literary merit? And of course the Turner prize often leads to discussions about the nature of art. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if a science prize could stimulate a similar debate about how science progresses, or on the details and relevance of particular scientific findings?

So how could a science prize generate the media buzz associated with the Turner or the Man Booker? One of the key characteristics of these prizes is that, at least partially, the judging is carried out in the public domain. A short-list is constructed and published in advance. So while the judges carry out their private deliberations, there is the opportunity for the media and the public to form and talk about their own judgements. These public verdicts don’t directly impact on the award of the prize itself, but they raise the profile and encourage active engagement with the content. I can imagine this working perfectly well for a science prize – a shortlist, perhaps a series of TV documentaries on each candidate, and then a big announcement. A potential audience of millions engaged with and inspired by leading-edge research, now that is a prize worth aiming for.

Presentation: Heads of University Biological Sciences departments

November 14, 2011

I gave a presentation on RCUK Strategy to the Winter meeting of the Heads of University Biological Science departments last week. Here are the slides, together with audio of my talk (direct link):

Sources

Slide 5: SET statistics 2011

Slide 6, 24: Royal Society, The Scientific Century 2010

Slide 7: Spending review 2010 [pdf]

Slide 8: Allocation of science and research funding 2010 [pdf]

Slides 14-19, 25: BIS/Elsevier, Performance of the UK research base 2011; Thompson-Reuters, Global Research Report UK 2011

Slide 26: Innovation Union Scoreboard 2010

Slide 27: Science, Technology and Industry Scorecard – Innovation and knowledge flows

Slide 28: OECD 2011, Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard – Public/private cross-funding of research

Slide 30: RCUK data principles

Slide 32: RCUK Concordat on Public Engagement

Slide 35: Times Higher Education

Slide 36: RCUK demand management principles

Slide 37: ESRC consultation responses

Slide 38: Nature

Patterns of UK research investment

October 18, 2011

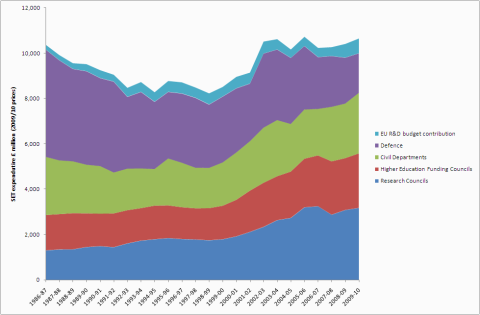

BIS published their annual ‘SET statistics’ last week, which provide a wealth of information on the UK’s investment in science, engineering and technology. The Campaign for Science and Engineering have published their take on the numbers. For me, one of the interesting aspects of the dataset is the reasonably long time series it provides, giving insights into long term trends. I compiled the following graph from the data to show how the general pattern of research investment has varied over time:

The investment levels are the inflation corrected figures, converted to 2009/10 prices. Some striking features of the patterns of investment are:

- In real terms, the investment in 2009/10 is equivalent to that of 1986/87. Total levels of investment have been reasonably constant in recent years.

- The changing pattern of investment has been towards increasing expenditure by the Research Councils and the Higher Education Funding Councils, largely at the expense of spending on defence. Spending by the civil departments has been steady and has increased slightly in recent years.

- Defence spending is more volatile than other areas with bigger year-on-year fluctuations.

I would be interested in your views on the statistics, so please comment.

Book review: The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks

August 25, 2011

No one can spend very long learning about life science without hearing about HeLa cells, but the story behind this cell line – where the cells came from, why they behave the way they do, and even why they have been so useful scientifically and medically – is more of a mystery. It is this story which Rebecca Skloot (@RebeccaSkloot on twitter) tells in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

I approached this book with high expectations, given the praise and awards it has received. And on one level I was not disappointed. The human story of Henrietta Lacks and her family is compellingly told and the fortunes of Henrietta’s immortal cells are drawn into sharp contrast with those of Henrietta herself and her descendents. The book also contains some fascinating portraits of the scientists and clinicians involved in the story. It would have been very easy to portray these (mostly) men in a negative light but Skloot manages to strike a balance between their laudable motives, the influence of business and an often amazing lack of concern for the donor of the cells and her family. The story of the scientists is a vignette of the complex motives that underpin research, a case study to disprove the idea that research is a cold, objective activity carried out in isolation from the pressures of the world.

I also think Skloot deals very effectively with many of the complex ethical issues surrounding the use of human subjects and tissues. The lack of appropriate regulatory safeguards as the new research into human cell lines developed is striking, especially given the tight restrictions on using human tissue and the requirements for consent that now operate. On one level this is shocking but also reflects the challenges of ensuring that regulation keeps pace with technological developments. And I couldn’t help but have slightly mixed feelings on this point. Would the research have progressed so quickly and effectively had there been a comprehensive and effective regulatory system in place? Of course we can never know, but given the apparently unique properties of Henrietta Lack’s cells, had she or her family refused consent many of the benefits that came from the research would have arrived much more slowly. These are complex ethical questions.

There is much to enjoy in this thought-provoking and well written book. But I can’t help thinking there is also a missed opportunity. I was disappointed not to learn more about the science of HeLa cells. What is special about them? How have they been used in research? What are they telling us about how non-cancerous cells divide and grow? Issues like these are not explored in any detail: for me the book over-emphasises the human story, interesting and compelling as it is, without providing enough of the science. This is just a personal preference, though, and I would certainly encourage anyone who is interested in the relationship between research and society to read this book.